next generation asthma care

exploring the transformative potential of citizen driven data towards the development of a new model of care for Asthma in Scotland.

‘Next Generation Asthma Care’ aims to introduce a predictive and personalised care model, utilising next generation technology to track medication adherence and other contextual data, in order to inform preventative approaches to asthma care. The DHI proposes that a service model that utilises digital tools and services - such as smart asthma inhalers that communicate directly with the cloud - could reduce cost and improve accuracy of data.

We employed a participatory design approach to collaborate with key stakeholders including people who have lived experience of asthma, and health professionals who deliver care for people with asthma, in order to inform a future vision for asthma care. A series of semi-structured qualitative interviews were first undertaken and the insights gathered were used to create ‘real personas’ from which to design speculative responses. This work informed two co-design workshops, which respectively aimed to design the preferable future for asthma care, and to understand user needs and required assets for an interactive asthma action plan designed to support self-management.

This report presents the findings of the design research activity undertaken, including insights into lived experiences of delivering and accessing services, challenges and opportunities to inform future models of care, and recommendations about how digital innovation might support the future delivery of asthma services.

Recommendations

Transitional learning points

Strong communication between teams and patients is critical. For example, transitional learning points which focus on early intervention through childhood, are necessary to enable education and self-management. Strong communication between points is critical, for example transition clinics which should have overlap and engagement between respiratory consultants and paediatric services. The role of the third sector and specialised charitable organisations could be strengthened in order to provide tailored education and support, delivering the right information at the right time in order to offer a more meaningful and effective service provision that is less reliant and secondary care provision.

Inhaler Adherence & monitoring

A step up/ step down service, which allows for clinically supervised support delivered by third sector, peer or independent groups could enable a more tailored service based on level of need e.g. first line support for lifestyle advice or proactive outreach when someone is at enhanced risk. This could also incorporate tailoring and personalisation of advice to address specific symptoms. It was recognised that each person has individual motivations and in order to support adherence and compliance, finding ‘the hook’ for each individual could enable better self-management. For example, devices such as inhalers which deliver an instant response. Education was seen as important in supporting adherence and inhaler use as was the role of visual communication as a way of improving engagement.

Transforming appointments

Participants described the current service as non-responsive, where being seen routinely is of little benefit and the annual review was seen to be unnecessary with appointments being cancelled due to exacerbation of symptoms. Instead contact could be based on the need demonstrated by citizen generated data, potentially allowing for a more accurate diagnosis and understanding of each individual’s contextual triggers. Through accessing specialist care in this way, significant delays in diagnostic testing could be reduced. For example, virtual clinics which are responsive to insights generated from data could allow patients to be seen by a specialist when they are experiencing symptoms rather than a patient having to cancel an appointment.

Asynchronous clinic

Through the use of more meaningful data exchange, an asynchronous clinic could achieve the same data exchange and outcomes as a face to face appointment via messaging and alerts over days or weeks which is more tailored to need and a more accurate reflection of condition. Asynchronous communication allows data to be transmitted intermittently rather than as a steady stream typical of a face-to-face consultation. This type of conversational agent is more convenient as they do not require both parties to be available in order to have an ongoing conversation. For example, citizens highlighted various apps and note taking methods they used to relay events and trends at their next appointment. With an asynchronous clinic, patients could send a message directly to the clinic which could triage the severity and sign-post to advice or a specialist appointment, potentially reducing the amount of outpatient and emergency appointments required.

Single Place for Data Storage and Pattern Identification

In order to effectively monitor the range of data required, users need to be able to combine their own technology and methods into a single place to allow them to determine patterns and actions. Currently people use diaries, and a move to digital alternative means that they should be able to set up their own ‘rules’ e.g. when weather is cold, and I cough a lot, I am ‘amber’.

Trusted and accessible data sharing (inc. managed expectations)

There emerged an overarching theme around why data was to be collected, what kind of data, what data sources, who the data was for and how it would be transferred. Real-time data monitoring and capture was discussed as a way to inform and manage care through a personal health record that both citizens and health professionals could contribute to and review when necessary. For example, consultants could benefit from pharmacy data that indicates when a blue inhaler has been dispensed. This can be indicative of patient condition and was seen to be of more value than prescription information alone.

Personalised normal baseline

In order for future interactions to be more beneficial the service should be responsive to the individual. This should begin by using data to build an individual ‘normal’ baseline of a person, including lifestyle information, goals and aspirations as well as their asthma. Such a baseline could include multiple data points and also recognise contact with health professionals as touch-points for data capture. For example, through combined data sets representing fitness and asthma, a broader understanding of the person can be drawn, allowing health professionals to make a more accurate diagnosis and better medication decisions.

Triggers for Responsive Appointment System

If a person can curate their baseline and trigger data in this way, then this can be used alongside clinical data to jointly agree personalised thresholds and triggers between green, amber and red zones. Once the system recognises personalised risk, routine contact (e.g. annual review) can be replaced by responsive appointment system – giving those that are in the amber zone quick access to nebulisers or clinical appointments.

Trigger monitoring

Regular monitoring technology (e.g. Strava) could provide an overview of asthma including inhaler use, prescriptions, and exercise. In addition, as part of the normal baseline, patients could define parameters outlining the data to be gathered passively e.g. weather, along with data which is actively collected in relation to their broader life and goals.

interactive asthma care plan

The focus of an interactive care plan is on quality of life and recognising what is normal for an individual in order to create a relevant baseline. Through dynamic discussion and shared decision making, an interactive care plan could be developed for and by a ‘circle of care’ to help the patient. This could also set out a control mechanism for meaningful data and provide a safety net for people with asthma through trend identification. A more person-centred action plan can change the relationship dynamic and encourage responsibility through having better understanding of what is medically possible to improve condition and what the person themselves can influence, e.g. weight and exercise.

Recognition of Non-clinical Thresholds

There are limitations to the ‘one size fits all’ set of thresholds in the current asthma plan. If you have non-clinical methods of determining your risk zone (red, amber, green) then many support tools and clinical services struggle to cooperate. For example, exercise tolerance or amount of coughing or air quality are not likely to have a formal bearing in asthma co-management tools at present.

Feedback Loops

Data can play a role in the personalisation through the provision of feedback loops to ensure that the dialogue between patients and health professionals could be more effective and meaningful. For example, having open appointments rather than fixed annual reviews enables the patient to access care as and when needed, which is triggered by the data and reduces the need for cancellations, unnecessary review appointments and emergency out of hours care.

App to Support Self-Management and Conversations

Through the gathering of their personal data, users can then use such a care app for self-management purposes and create a record that they can share with clinicians to help explain how they are doing at review, allowing for a more meaningful and personalised conversation.

Remote Monitoring Service

A remote monitoring service that recognises and communicates with users when they are amber to give them confidence or help them manage in the moment (rather than waiting weeks for an appointment) has potential to reduce strain on current services.

background

Asthma is now one of the most common long-term conditions in the UK (Mukherjee et al., 2016) and within Scotland prevalence is 9.51%, representing approximately 554,306 people (Asthma UK Data Portal). Self-management is recognised as an established and effective approach to controlling asthma however the uptake of such practices is low and poor control of asthma is understood to be a significant factor in over 50% of cases (Miles et al., 2017).

It is acknowledged that a significant proportion of the morbidity and mortality around asthma is preventable, for example; two thirds of asthma deaths are preventable through better basic care. (Royal College of Physicians, Why Asthma Still Kills, 2014). Similarly, asthma co-management has the potential to be significantly improved through the utilisation of technology and service redesign to create a data rich environment. While the use of technology as a driver for encouraging better self-management is recognised (Miles et al., 2017), adoption may be limited by the digital-skills capacity of the individuals involved as well as significant challenges around trust, data collection and ownership and the associated system architecture. Through combining the Digital Health and Care Innovation Centre’s (DHI) broader work around citizen generated data and the condition expertise of Asthma UK, this project explored new models of care for asthma that enable people to self-manage effectively and can contribute to a meaningful, and sustainable care pathway.

objectives

The planned objectives for this project were:

To explore the transformative potential of citizen driven data towards the development of a new model of care for asthma in Scotland.

To develop a current state map of the provision of asthma care in Scotland, drawing on experiences of key stakeholders (health professionals, patients, community, third sector) and the research data of Asthma UK.

To create a rich asset base of citizen driven data models and the associated use cases.

To co-design outputs that extrapolate those assets and shape new working practices, prototype technological developments and frame a preferable future model of asthma care and self-management.

To provide additional supporting evidence and content to Asthma UK with which to develop a vision, alongside evidence-base and compelling visual materials around the future of digital asthma care that can be used to leverage future funding opportunities.

To create a compelling health and care use case for next generation connectivity in Scotland, demonstrating to the Scottish Government the benefits of investing in the required networking infrastructure and attracting inward investment into Scotland using asthma as the index condition.

METHODOLOGY

Adopting a research approach that utilises participatory design methodologies, this project included a design planning workshop, literature review, qualitative design interviews and two co-design workshops.

LITERATURE REVIEW

A literature review was undertaken in collaboration with the DHI research and knowledge exchange team. This review explored the current context of asthma care in Scotland, drawing upon existing research and insights from Asthma UK. The output from this review formed the basis of a position paper (Chute, Hepburn and Rooney, 2019), setting out the basis for the NGAC project. The position paper has been published and is available to download on the DHI’s website.

QUALITATIVE DESIGN INTERVIEWS

A series of six semi-structured qualitative interviews were undertaken with people who have lived experience of asthma and a further four interviews with health professionals who deliver care for people with asthma. Each interview was attended by two members of the research team and took place in a location of the participant’s choice, last approximately one hour. The interviews were framed around a design tool that aimed to capture and visualise the discussion. This worked to engage participants and created a focus, or boundary object (Johnson et al., 2017) through which to navigate and map the discussion of rich lived experience.

When analysing the data, the mapping was visualised and reviewed alongside the verbatim transcriptions of audio recordings. This was used to generate real personas and contributed towards a current state mapping of asthma care. While not intended to be generalisable or representative of the Scottish population, the personas and current state mapping provide rich insights into the lived experience of asthma and offers real-life scenarios and use-cases from which to design speculative responses.

CURRENT STATE MAPPING

Current state mapping offers insightful overview of the ways in which a current service is delivered or experienced, similar to a service blueprint or process diagram. Within the context of digital health and care innovation, current state maps present a snapshot of the service model as described by the health professionals interviewed, and as perceived by those people accessing services. It is acknowledged that the delivery of services can differ across geographic health board areas and as such the current state map cannot be generalisable nor does is it representative of all stakeholders. However, it does provide a rich overview, highlighting opportunities and challenges experienced and offering a way to better understand, explore and innovate within a given context.

co-Design workshops

Co-design workshops provide a space for trans-disciplinary collaboration, bringing together disparate stakeholders to generate deep insights; enhance their understanding of a particular context; and imagine solutions to emerging challenges. Invited stakeholders can include services users; public citizens; academics; and business, public, private and civic sector partners. The co-design approach is person-centred, driven by design methodologies and can engage participants in a series of activities such as observation, brainstorming and prototyping ideas. In this immersive and iterative environment, participants can quickly progress thinking through making, reviewing and refining ideas towards an informed final outcome that can be tested. Two co-design workshops were hosted in the DHI’s Demonstration and Simulation Environment (DSE), bringing together participants who had lived experience of asthma with professionals from health, policy and Asthma UK representative.

The first co-design workshop focused on designing the preferable future. Three key activities took place: the first activity asked participants to review and comment on the pre-produced personas, identifying any common themes emerging; the second activity was a walk-through of the DSE, where participants were exposed to existing and near-future examples of digital innovation across health and care; and finally, the third activity asked participants to identify a key challenge from those emerging in activity one and to co-design a preferable future or solution that could address the challenge.

The second workshop aimed to develop a greater understanding of user needs and required assets for future asthma care which supports self-management, with a focus on the functionality of an interactive asthma action plan. The discussion was centred around a ‘base layer’ template to represent the asthma action plan, with zones to indicate red (Need urgent help), amber (need some help) and green (well). Through using the personas, participants were asked to map the different components on to the action plan and consider: what data blocks might be generated or required; how might we measure a personalised ‘normal’ baseline; and what else the action plan should do in order to enable personalised functionality. Participants were then shown examples of self-monitoring and habit building digital platforms and asked to prototype their own care coordination tool which outlines what data they would monitor, what data they would share, with who and for what purpose.

FINDINGS

emerging themes: current state mapping

education for self-management

A common emerging theme among health professionals was the lack of self-management. Described as poor self-care education in relation to the condition, participants suggested that this has a significant impact on the level and kind of engagement people have with the healthcare system. An example highlighted transition clinics as a critical point of the asthma education journey, yet there is a perceived lack of engagement between respiratory consultants and paediatric care.

lack of ownership at primary care level

Participants described the requirement for all GP practices to identify an asthma lead and to take ownership of asthma at a primary care level. However, contrary to current asthma guidelines, not all GP’s have a lead in place and where there are leads, these are not always visible. Additionally, participants described an over-reliance on secondary care referrals as a route for asthma care and it was discussed that many of these patients could be managed within primary care alone, stating that the overall goal is to return a patient from secondary to primary care.

problems with prescribing

At a secondary care level, consultants do not always know whether prescriptions have been dispensed or how frequently. Having access to this data could highlight challenges in relation to asthma adherence and self-management and create opportunities for early intervention. Another challenge described by participants was an apparent over-reliance on emergency prescriptions among people with asthma, for example short-acting beta-agonists; an inappropriate or lack of use of steroids; and a poor self-awareness among patients of their own prescriptions.

Similarly, there are often differences between the type of prescriptions issued by health professionals, for example inhalers issued by GP, hospital wards, and at asthma clinics. The delay in accessing and updating patient records can create a challenge, particularly when tracing whether a client has had a positive or negative response to the prescription.

the challenge of co-morbidities

The additional challenge created when asthma patients present with multiple conditions and co-morbidities was discussed. This results in increasingly complicated asthma and a high number of referrals to the difficult asthma clinic. Participants also indicated a higher proportion of women within the difficult asthma clinic alongside increasing prevalence of obesity.

a need for speciality care

Participants described that access to specialist care can be a challenge, in particular access to nurses with an asthma diploma. Similarly, participants discussed the difference between accessing a generalist health professional and an asthma expert, and the subsequent delays this could create with regards to diagnostic testing. Additionally, participants also described the need for speciality care to support compliance, adherence and concordance among people with asthma and in particular the need for pulmonary rehab.

emergency as routine

Similar to the over-reliance on emergency prescriptions, participants also described an over-reliance on emergency services and secondary care responses. This was described as revolving-door patient admission, whereby a patient would present to the out of hours GP and/or ambulance, be treated in the emergency department and then self-discharge when they are feeling better. While participants agreed that they are keen to avoid unnecessary hospital admissions, they also discussed the low attendance at follow-up appointments after an emergency admission and poor attendance at out-patient clinics.

“If you speak to patients, the thing they find most beneficial is having someone to talk to and support them when they’re unwell, and that’s usually nursing.”

”

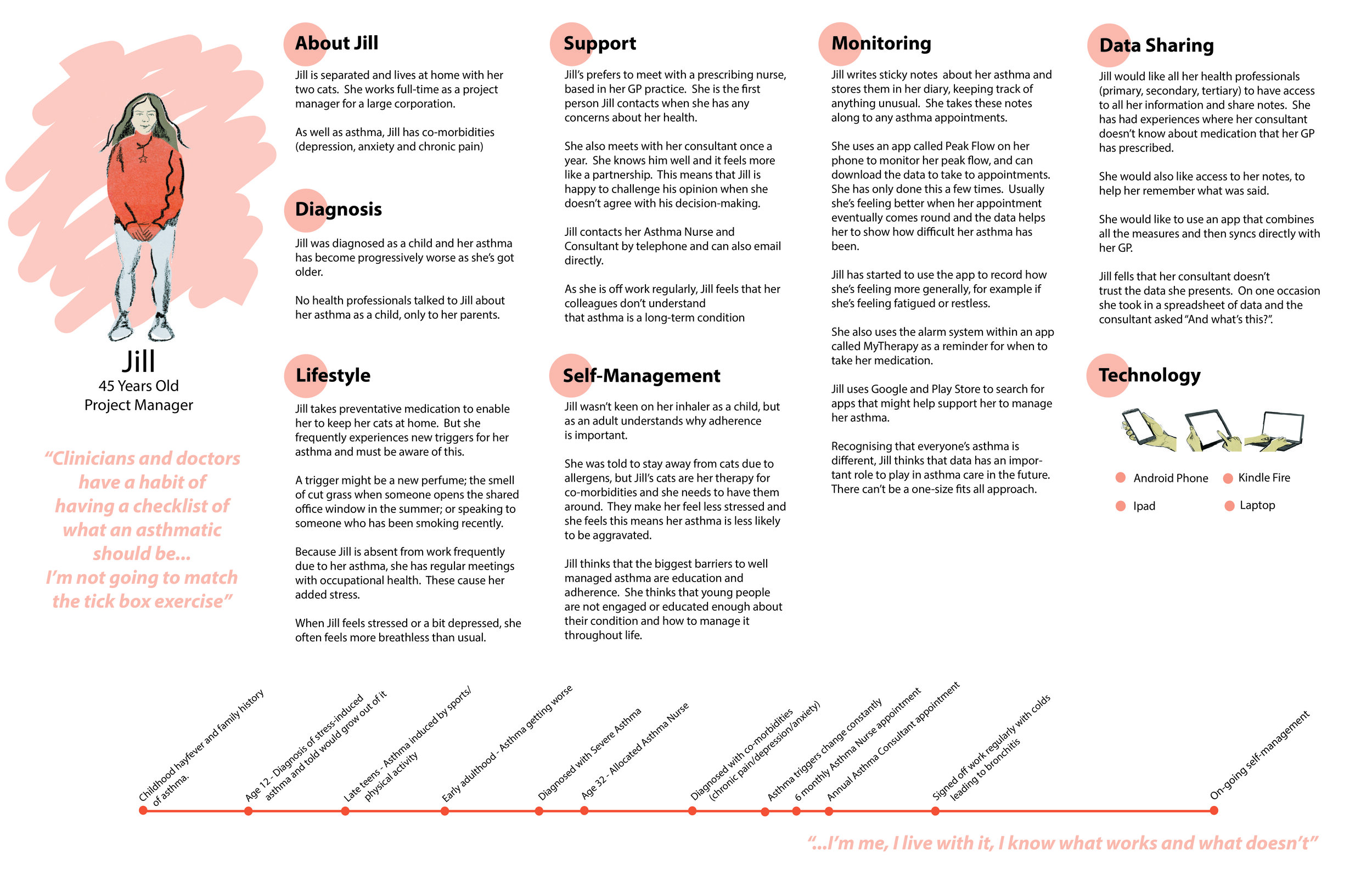

lived experience personas (citizens)

The interview data was also analysed and developed in to a series of personas. Each persona featured a pseudonym and key personal data (age, job title) has been altered slightly to protect the identity of participants. Personas aim to capture real lived experience of participants, generating data for use-cases for the demonstration and simulation environment to test potential digital interventions.

A number of key themes emerged from the initial analysis of the interviews with people who experience asthma which framed the first iteration of personas:

Diagnosis

The challenges around methods of diagnosis were highlighted and in particular the problems associated with a prolonged un-diagnosis or suspected asthma diagnosis. Suspected asthma was described as manifesting in and as a number of associated conditions, requiring an awareness of co-morbidities.

The transition from parent-managed asthma to self-management as an adult also emerged as a challenge, particularly when participants had low interaction with asthma education as a child.

“The asthma came back...I had lots of problems getting an inhaler to work so it took a while to get back under control.””

lifestyle

The balance of maintaining a lifestyle of choice and managing asthma emerged as a significant insight. In particular, participants referred to the planning and risk assessment required to support lifestyle choices. Participants described fitness as important however discussed the challenges inherent with living an active lifestyle to keep healthy. This included having to carefully consider the impact of external and environmental factors such as pollen and air quality before participating in outdoor activities.

Similarly, asthma was described as a burden and a barrier to maintaining the lifestyle participants desired, reflecting a degree of resentment toward the condition when it had curtailed expectations. The wider impact on social life and the additional stress placed upon family also featured heavily in the findings. Participants described feelings of guilt and responsibility, particularly when family members take on a caring role. The challenge of conflicting clinical advice relating to lifestyle also emerged, particularly when participants described being told not to undertake a particular activity due to the risk of exacerbation. This was also considered in regards to managing asthma within the workplace.

“The most important thing, I think, is being aware of what can cause problems, avoiding what can cause problems or operating in such a way that it minimises the problem””

support

The importance of meaningful interaction with health professionals emerged, with participants referring to key relationships developed over time however there was also a demand for a more joined up approach between primary and secondary care systems. Participants discussed key points in their engagement with health professionals, with the annual asthma review emerging as a key touchpoint. The impact of having asthma as an employee emerged as a challenge, with participants describing the stress caused by having to repeatedly call in absent from work due to the condition.

Participants also acknowledged the support of family however an insight also emerged relating to low asthma awareness amongst friends and family, particularly in relation to potential triggers. The value of support provided by third sector and charity organisations also emerged, signposting to other agencies where required.

self-management

Overall participants reported a tendency to manage their condition based upon symptoms rather than existing tests such as peak-flow. This information was often recorded in disparate locations but not necessarily shared with health professionals. Managing the condition was described as challenging, with multiple inhalers, pre-emptive antihistamines and co-morbidities adding to the complexity. Whilst the annual asthma review and care plan was mentioned, this wasn’t used as a mechanism for managing the complexity or for recording data relating to symptoms. Paper-based notes and correspondence emerged as the main approach although digital access was preferred.

Similar to the insights emerging in diagnosis, the limited educational opportunity around asthma care in childhood was understood to contribute to poor self-management in later life. There was also an emerging insight around the importance of education to support adherence and inhaler use and the role of visual ways of engaging people to ensure compliance.

“I don’t always do peak flow readings...But I know, mentally what to do, if the symptoms are getting worse I know when to double my inhalers up””

data-sharing

Key insights emerged around low trust in citizen data when health professionals are presented with this during appointments. Having no personalised health record that represents the patient perspective, combined with increasingly medicalised proforma processes was reported to contribute to fragmented and disjointed understanding of asthma and asthma care provision.

Real-time data monitoring and capture was discussed as a way to support informed decision-making, delivered as part of digital asthma care plan. Similarly, the use of technology to monitor triggers such as air quality to support planning and risk assessment also emerged. Overall, poor integration across the systems used by health professionals involved in asthma care emerged, resulting in unnecessary appointments.

monitoring

There was a significant challenge emerging in relation to the personal paper-based notes and records and how these might be converted into useful and accessible data to support improved care. Monitoring was also described as a way of remembering, particularly in relation of medication and questions to be asked at forthcoming appointments. Recognising the importance of self-assessment of health and asthma, there was also an insight around the potential value of combined data set, for example fitness and asthma monitoring to provide a meaningful overview or baseline of the individual.

“...you always forget everything. The number of times I go to a clinic appointment and I think ‘oh, I must ask them this’, and then afterwards you go out and my mum’s like, ‘did you ask about...?’

”

lived experience personas (health professionals)

From the interviews with health professionals, emerging themes were:

secondary care

The secondary care services predominantly support those with more uncontrollable or difficult to manage asthma conditions. Core practices focused on stabilising the patient in order to refer them back to primary care. This entails accurate diagnosis, education and symptom management through the specialist triage service (hospital visits, home visits and clinics with the specialist health professionals (consultants and nurse). The well-established telehealth programme offers succinct care in the community for COPD. Through the application of digitised data collation and remote specialists monitoring, accurate support services are offered via a traffic light system (amber –red). This approach has enabled patients to remain at home, alert practitioners when there is a need for calls and visits which ultimately reduces hospital admissions. Participants suggested that a similar service could be adapted to include asthma as the conditions can overlap. However, the growth in community-based care is placing a strain on health professionals, who feel their time spent in the community keeps them away from delivering the type of patient care required in hospitals (e.g. limited hospital visits and time spent on these visits).

referral

In theory patient referrals are managed through primary and secondary referral processes. Primary referrals in general are through a GP appointment after an episode of breathlessness. Secondary referrals are made through a number of avenues; when primary care is not being managed well; if a patient is newly diagnosed with acute Asthma after an A&E visit; and/or if their asthma changes. However, in practice ‘systemic issues’ are evident between and across the asthma care service(s) (primary and secondary) due to variances in organisational management models and a lack of continuity in record keeping and data sharing. For example, specialist consultants found GPs may not flag up an increase in a patient’s asthma related A&E visits. As this is a trigger for referral to secondary care (specialist nurses & consultants), this lack of accuracy in shared data between practitioners impacted upon the ‘continuity of care’ offered by the health service ecosystem. The use of A&E as part of this ‘system’ was seen as inadequate. This busy service was seen as inadequate in offering asthma patients a robust and continuous level of care they required.

primary care

With the majority of patients their condition is managed through primary care. There is a growing belief amongst health professionals that asthma patients are seeking a reduction in their medication, symptoms and hospital admissions. However, there is a lot of variation in service provision. For example, within the GP practices different models of how each practice manages asthma care was apparent often with no lead at the practice.

data sharing

There was an emerging challenge around the increasing amount of data being created and how it could be used. Health professionals suggested that within the current model the patient caseload is already at the upper limits for many, so adding review of data to the workload could cause a significant additional burden. The simplification of data collation, sharing, and patient ownership of this data was a voiced by the practitioners but with differing perspectives. For secondary care provision, a personable approach whereby the practitioner develops a professional relationship with the patient, was seen as pivotal in building a professional-patient trust capacity. However, a simplification of data collation, visualisation of outputs, provided the system was financially sustainable and reliable was seen as beneficial in improving patient care and data management. The need for a more succinct and error proof data collation system, accessible to all (practitioners and patients) was seen as a positive move by practitioners. The need for ‘buy in’ from patients in a new system and service approach would be required. The opinion of success with a databased system was met with a mixed response in terms of demographics. The 50 years+ patients were already using digital systems in their management plans and seen as an ‘easier target group’. However, younger generations were disinclined to actively input data, suggesting wearable solutions may be more suitable.

technology

Current technologies are a mix of tools (paper, digital, telephony) with varying degrees of success. If efficiencies and improvements in asthma care are to be realised professionals expressed a need for technology to be simple and fit for purpose.

“I look after hundreds and thousands of patients. Am I going to have time, or who is going to have time to look at the data and in close to real-time say, “you know, your peak flow is a little bit down today, you should do this…?

”

key challenges

Though successful, the telehealth programme is not without limitations. An over reliance on digital intervention can make patients blasé towards their condition and awareness of self-management. Often those most in need are the least engaged (e.g. failing to follow asthma management plans and collect prescriptions).

Lack of patient understanding in terms of their condition and management needs, despite medical support in understanding these, was the biggest cause for concern amongst practitioners.

Human error in some of the techniques used in remote monitoring were of concern (e.g. peak flow monitoring, administering inhalers).

If additional learning were possible to improve awareness in data recording, administration techniques and the use of data in asthma management then patient well-being could be drastically improved.

Practitioners felt resource and time constraints impact on the level of service delivered, often feeling overstretched. Succinct and effective ‘dovetailed’ services across the profession were highlighted as a growing need. Current service delivery relies upon the use of multiple organisation models and services (e.g. GP practices, consultants, telehealth, etc) which do not deliver a ‘streamlined’ service and leave a ‘holistic service’ open to error (human and systemic).

“7% of people are able to take their inhaler 80% of the time correctly.”

co-design Workshop One: Preferable Future

Exploration of Personas

Participants first explored the personas in more depth, and the emerging key themes were: data, interaction, education, and self-management.

Data: Building Blocks of Asthma

Data was described by the group as the building blocks of asthma, where participants discussed the different types of data; the purpose and the intended recipient. The role data can play in building up a rich picture of the patient was discussed, for example unfiltered information such as patient diaries was acknowledged for encouraging self-management and monitoring. However, participants noted the challenge in making this information useful and accessible for clinical staff and how this might impact on how time is spent during an appointment. There was also a concern that personal health data shared directly with health professional could have a negative impact on self-management, creating an over-reliance on the health professional to monitor and identify any emerging issues.

Data was also seen as a way to inform and improve the management of care, for example consultants could benefit from pharmacy data to know when a blue inhaler has been dispensed. This can be indicative of patient condition and was seen to be of more value than the prescription information alone. This was framed around the potential of a personal health record that both citizens and health professionals could contribute to and review when necessary.

The discussion also highlighted the notion of ‘feelings versus numbers’, whereby patients were offering a personal response to how they felt as a measure of their condition rather than using a clinical approach such as peak-flow monitoring. Participants recognised the value of medical-based metrics for reporting their condition however the value of the personalised monitoring and the capture of the subsequent data relating to how people are feeling was considered important and was described as ‘sensitive measures’.

Refocusing the use of data, participants discussed how each individual’s experience of asthma is variable and as such, blanket asthma management is not possible. In response, participants considered whether an individual ‘normal’ baseline could be enabled through data to present a personalised picture of asthma. Such a baseline could include multiple data points and could also recognise contact with health professionals as touch-points for data capture.

Similarly, participants recognised the extended role of data in the personalisation of triage by ensuring that patient records were quickly accessible; in the provision of feedback loops to ensure that the dialogue between patients and health professionals could be more effective; and in the delivery of advice and education for appropriate and timely asthma care. Overall, the value of data within asthma care was acknowledged however, there was an overarching question around why data was to be collected, what kind of data, who the data was for and how it would be transferred.

Education

Participants placed significant emphasis on ensuring that people with asthma were capable and equipped to manage the basics of asthma care. In particular, participants focused on inhaler use. Poor inhaler technique was described as one of the main challenges in asthma care and despite the adoption of interventions aimed at addressing this (for example educational videos, interactive instructions and inhaler-based alarms), challenges still exist. Such interventions do not always give feedback to the recipient, and where they do this is not immediate.

Similarly, action plans emerged as an area of interest to participants. At present, asthma action plans are paper-based, with patients retaining a physical copy at home. Participants remarked that everyone involved needs to have access to and understand each patient action plan in order to support adoption and adherence. There was a query as to whether the current infrastructure could manage an increased volume of plans and offer interactive capabilities.

Transitional learning points were also an area of discussion, with a focus on early intervention through childhood. Similarly, there was discussion around the potential role of the third sector and specialised charitable organisations in providing tailored education and support, the right information at the right time in order to offer a more meaningful and effective service provision.

Interaction

Interaction between HCP’s and patients was a strong theme throughout however this was not focused around face-to-face engagement. Rather there was a shift towards managing interactions with health professionals in a way that suits the needs of the individual, for example replacing unnecessary appointments with digital messaging.

There was also an acknowledgement that the interaction is two way, with both citizens and health professionals responsible for contributing. In this way, both consultant and citizen have different aspects they can influence and control, for example the consultant is responsible for management of medication while the patient is responsible for managing their weight and fitness.

There was discussion around potential frustration both for the patient in not knowing how they will feel from day to day and the impact this has on all aspects of life, including attending asthma appointments. For the consultant, it can be challenging when appointments are cancelled due to ill health. This is because at that time they have an improved chance of working out what is wrong, what has triggered the patient to feel unwell and correcting the course of treatment accordingly. For citizens, a similar scenario emerged in relation to regular appointments whereby they may be feeling well on the day of the appointment but have spent the previous week suffering from an exacerbation.

Self-Management

This focused around what a patient can do to help themselves and the drivers of self-management which could be supported by health professionals. In particular, there was an emphasis on personalised advice, tailored to address the symptoms experiences as opposed to the treating of asthma as a condition that it equitable. In this way, the focus is on quality of life and recognising what is normal for an individual in order to create a relevant baseline. Key to this was a discussion around an interactive asthma care plan that could provide oversight of the citizen holistically, taking into account their lifestyle, co-morbidities, ambitions, as well as their asthma.

Despite recognising that education was important, in order for this to be meaningful it needed to be personalised, in a format that was accessible and should encourage self-management as opposed to creating an increased reliance on the health professional.

There was discussion around devices that could support self-management. This included sensors that could be triggered to monitor external influences such as air quality, or smart inhalers that could support adherence and compliance.

A Preferable Future

Participants then selected the theme interaction to take forward to build a fuller picture and explore a preferable future. They were asked to identify who the key stakeholders were and to reimagine what they would like interaction to look like in the future. The discussion centred around three main areas which are highlighted below, and the findings are discussed as part of Recommendations.

Transforming appointments: when people cancel appointments due to exacerbations and the annual review;

Who is the right person to see the patient?: considering medical hierarchy and patient disclosure, and;

The relationship with the consultant: the contextual impact asthma has on life; spheres of influence.

“Up to 48% of our time is on admin, which is shocking [we could reduce that to] 20%. ”

Co-design Workshop Two: Future Asthma Care Action Plan

Defining Requirements

Participants discussion focused on three key areas: data blocks, personalised baseline, and personalised functionality.

Data blocks: monitoring my asthma

The current asthma action plan uses peak-flow and inhaler use as the main quantitative trigger points for escalation. People can be in the ‘green zone’ when they are managing well, escalate up to the ‘amber zone’ when they are at some risk, and then further to the ‘red zone’ when immediate urgent action is needed. Each zone has guidance around symptom management, medicines use and other things that will help people to self-manage or call for help when needed. Triggers relating to air quality, allergens, pet hair and seasonal triggers such as pollen in spring/summer, or winter viruses were highlighted as data participants would want to monitor and which are not currently utilised as part of an asthma action plan.

There are multiple reasons for moving from green to amber zones, some of which could be automated and some which would require personal input. For example, bringing together and automating environmental data such as regional weather and temperature data, air particulate in the home and GPS location data could alert the user to identified risk factors and provide an awareness of the triggers that cause an escalation between green and amber zones.

The ability to monitor signs of becoming unwell was also understood as being useful with respect to self-monitoring. For this to be effective personal input from the user would be required. Participants discussed data such as cravings of ‘bad’ food which was out of their usual eating habits or contact with someone who has a cold.

Personalised baseline: measuring my asthma

Exercise was seen as important for participants to maintain fitness and a healthy lifestyle. This also helped them to manage their asthma but they were worried about the level to which they could push themselves without triggering an exacerbation. Clinical teams could not address this beyond the ability to walk. Meanwhile sports and fitness professionals could not create exercise plans that account for asthma.

The current clinical measurement of peak flow wasn’t seen as a useful or user-friendly method of measurement to participants. Although it was understood as an assessment of their ability to breathe and function normally, participants were instead basing their level of wellness on physical ability such as effort and time going up stairs or swimming lengths in a pool. These personal measures of ‘what well means?’ to each person necessitates a more person-centred mechanism for capturing their data and goals.

Balancing what is clinically ‘well’ with lifestyle choices was also key to participants in establishing a personalised baseline, for example owning cats, which would not be recommended for some asthmatics.

Personalised functionality: Sharing my asthma data

Participants discussed a need for digital communication with Health Care Professionals to reduce GP and hospital visits and being able to share data that could inform their care. For example, when in the amber zone, it may be possible to share blood oxygen data with a clinical service during the night, alongside a prompt for feedback and advice to the patient e.g. increase reliever, see GP in morning or call an ambulance.

Similarly, participants also discussed the ability for a system to learn about their asthma, how different variables interact and establish an upper threshold and personal preferences. For example, a smart system could consider combinations of personal triggers or other health conditions to suggest a preferred course of action.

“If it’s combined with respiratory infection, I know that so I can go to the hospital, but if it’s just cold air or air quality I’m more towards staying at home than going to the hospital.””

Exploring the Persona Prototypes

Participants then developed rough prototypes of an interactive care plan that would enable them to self-manage through curating their own digital assets and allow the creation of rules indicating how, when and with whom this is shared.

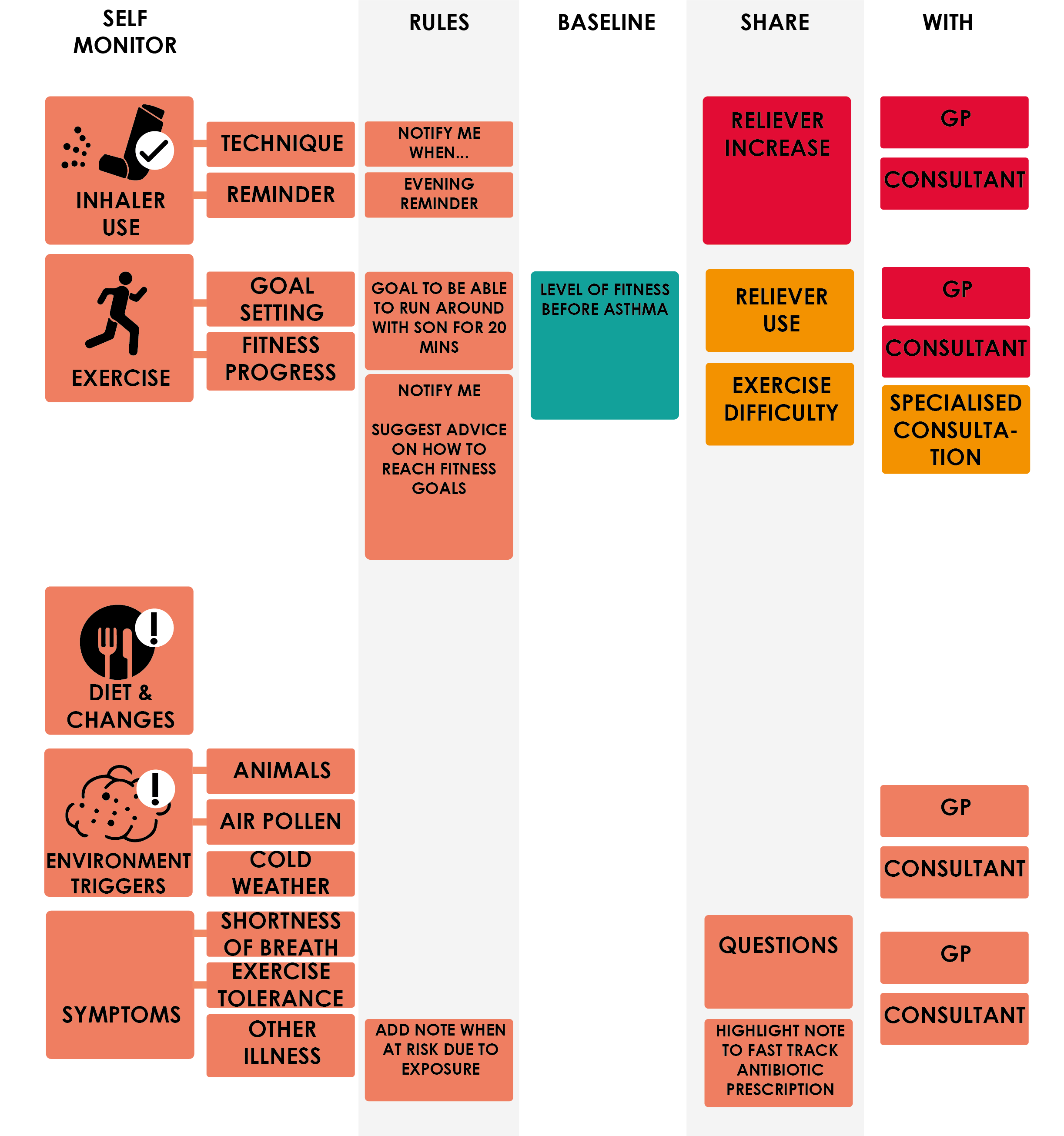

Persona: Ronan

Ronan considers his asthma as easy to manage and is mostly in the well zone of his action plan (green). As well as monitoring environment data so he can plan around his triggers and set reminders for his inhaler Ronan would also like feedback on his inhaler technique. Ronan’s main motivation is around his fitness level. He has always been interested in health and fitness and wishes to track his progress and set goals so he can regain a level of fitness to allow him to be able to run around with his son without fear of becoming out of breath.

Ronan prototype

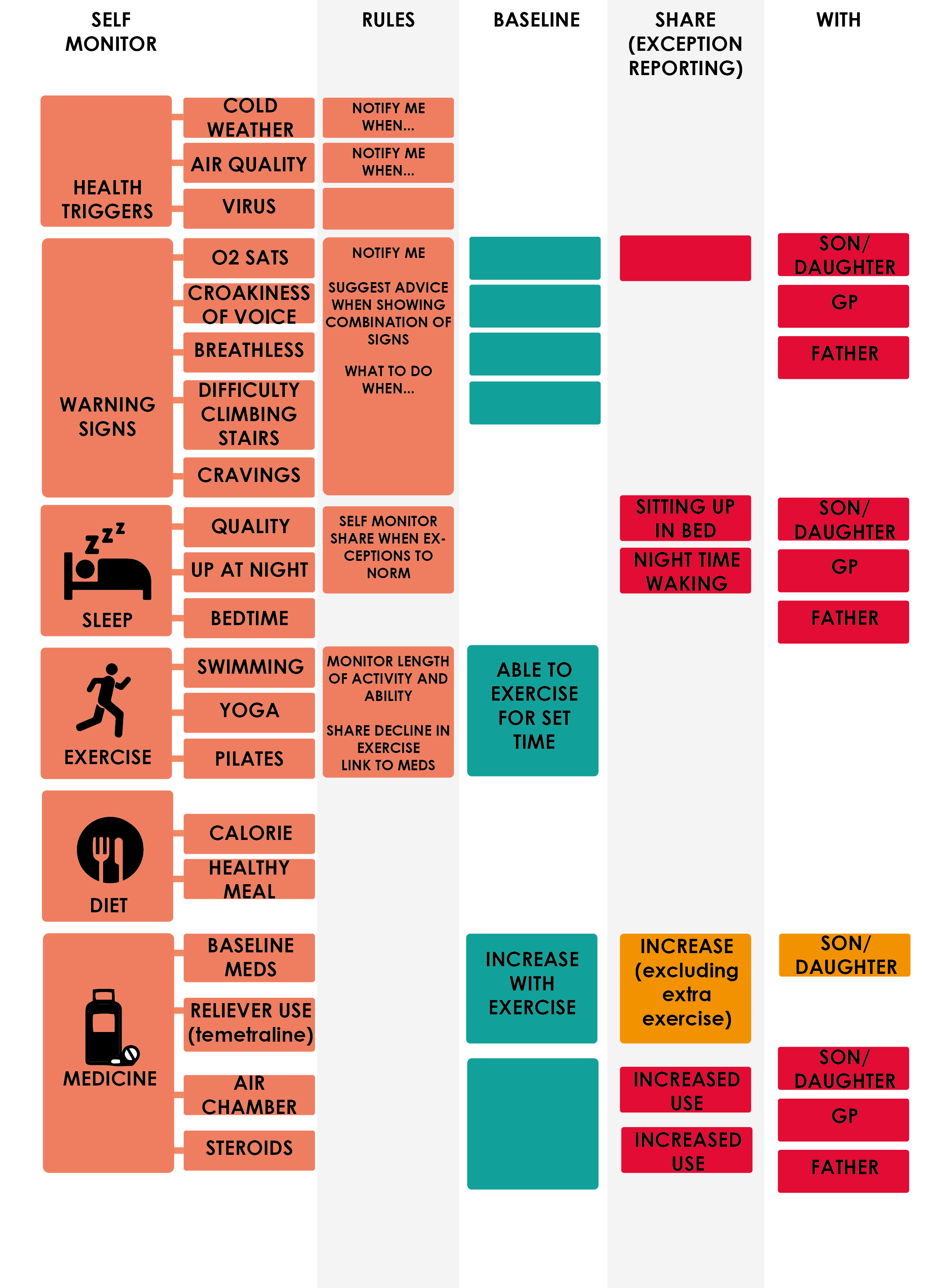

Jill prototype

Persona: Jill

Jill has complex to manage asthma as well as other long-term conditions which make GP and emergency hospital visits a regular occurrence - meaning self-management can be challenging. Jill acknowledged the importance of sleep, diet and exercise in keeping her well and the relationship with this data, her asthma triggers and medication as key in managing her condition. She uses indicators that she is in her well (green) zone such as being able to swim or climb stairs as a way of monitoring her baseline but as she has multiple conditions, a decline in exercise does not always result in a move between zones so it is important to be able to set rules related to a combination of data. For example, an increase in her reliever is actually an indication of being in the green zone as this indicates she is able to exercise more. However, an increase in reliever without the increase of exercise could be an indicator that she is in amber or red. In these cases, Jill would like to receive notifications of what to do when, for example if she is having exacerbated symptoms overnight and if she is unsure at what point she should contact a professional. She would also like to notify close family of incidents that take her in to a red zone.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all of our participants for giving up their valuable time and for generously sharing their thoughts and experiences of asthma care. We are grateful to Asthma UK for supporting recruitment and this programme.

Finally, we would like to thank our colleagues at the GSA and DHI for their support with the workshops and analysis, and for undertaking desk research to aid the project.

Digital Health and Care Innovation centre

The Digital Health and Care Innovation Centre (DHI) is a partnership between the Glasgow School of Art and the University of Strathclyde. The DHI aims to bring together health, care and third sector professionals, academics and industry partners to work together to develop innovative ideas to overcome health and social care challenges.

Authors

Don McIntyre, DHI Design Director, GSA Innovation School

Dr Leigh-Anne Hepburn, Research Fellow, GSA/ DHI Design Team

Angela Bruce, Research Assistant, GSA/ DHI Design Team

Chal Chute, DHI Chief Technology Officer

Related publications and references

Chute, Chaloner, Hepburn, Leigh Anne and Rooney, Laura (2018) Next Generation Asthma Care Position Paper. Digital Health and Care Innovation Centre (DHI).

Johnson, Michael Pierre, Ballie, Jen, Thorup, Tine and Brooks, Elizabeth (2017) Living on the Edge: design artefacts as boundary objects. The Design Journal, 20 (Sup 1). S219-S235. ISSN 1460-6965

Mukherjee et al. (2016) The epidemiology, healthcare and societal burden and costs of asthma in the UK and its member nations: analyses of standalone and linked national databases. BMC Medicine, 14:113

Miles et al (2017) Barriers and facilitators of effective self-management in asthma: systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient and healthcare professional views. NPJ Primary Respiratory Medicine. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/414737/2/s41533_017_0056_4.pdf

Royal College of Physicians (2014) Why Asthma Still Kills, The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD). https://www.asthma.org.uk/getinvolved/campaigns/publications/survey/

Contact: A.Bruce@gsa.ac.uk